To gather data successfully from what we observe, we cannot assume anything—including who someone is—based on a feeling, a look, or what we might have experienced in the past. Likewise, moving too quickly or too early in many situations—implementing a solution to a business problem, reprimanding an employee, or walking away from a relationship—without confirmation of the facts can be detrimental and in some situations fatal.

During the Westgate Mall siege in Nairobi in 2013, captive shoppers who incorrectly guessed the identity of the armed men they encountered paid dearly. Police, helpful citizens, and the attackers were all armed and dressed similarly, since terrorists often don official-looking uniforms, and many undercover officers were wearing casual clothes. Survivors who hid inside the Nakumatt supermarket recounted how after several hours a group of men with guns arrived at their location, proclaimed they were rescuers, and urged shoppers to come out of hiding. Those who did emerge, grateful, arms raised, were shot down by the untruthful terrorists.

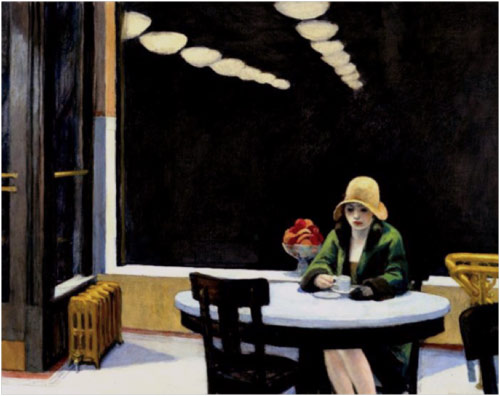

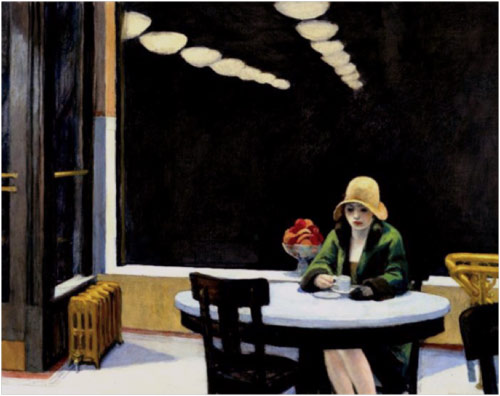

We must ensure that when we draw conclusions, we are using only facts, not opinions. Look at the painting below. Would you consider the following sentence a valid summary of it? A forlorn woman sits alone in a coffee shop at a round, white, marble table.

While it might read well, it is, in fact, full of assumptions. The sentence reaches the conclusion that the woman is forlorn, an adjective that means lonely or sad. This is a subjective interpretation of the woman’s expression, not a statement of fact.

The sentence also concludes that the woman is sitting in a coffee shop, despite a lack of proof to the positive. She could be in a bookstore or hotel lobby.

A better, more objective summary of the painting would be: A woman with a closed mouth and downcast eyes holds a cup and saucer while sitting alone at a round, white-topped table.

This new sentence describes the woman’s face and countenance based on objective facts—she’s looking down, her mouth is closed—without adding any assumptions about her mood. It also factually states that the woman is holding a cup, without guessing what type of place she is in or what—if anything—is in her cup. What’s the big deal with “coffee shop” versus “holds a cup”? A lot. Where she is hasn’t been proven or disproven. To state something as important as location as a fact, even casually, especially to someone unfamiliar with the scene or someone down the chain of information, can lead to more untrue assumptions that turn into “facts.”

Even subtle differences between subjective and objective conclusions can be crucial. In describing the painting, while “a round, white, marble table” and “a round, white-topped table” are just one word off, it’s an important word. That the table is made of marble has not been proven; it’s not a fact. It could just as easily be painted wood or Carrara glass. The first description also states that the table is “white” and “marble” but doesn’t signify how much or where. There is a marked difference between a table that is all white and one that is just white-topped, as well as one that is made entirely out of marble or just topped with it.

Does it matter what a table is made of? It could matter a great deal. Noticing the composition of an object saved the life of Goran Tomasevic and the policemen he followed into the Westgate Mall in Nairobi. The chief photographer for Reuters in East Africa, Tomasevic was hiding behind a large column with the police during a gun battle with the terrorists. When he noticed that the pillar wasn’t attached to the building and knocked on it, he discovered that it was hollow. He told his companions to knock on it as well, and they did, answering, “So what?” Tomasevic explained that the thin material wouldn’t stop bullets or offer the protection they were seeking. They quickly moved to a better-fortified location and lived.

We all make assumptions more often than we think, and like a snowball, even the smallest ones get bigger as they go downhill. The earlier the assumption is made, the more dangerous it is because it skews subsequent observations. Accuracy in the first stages of the observation process is critical. If you’re the eyewitness or the first person to get the news or the one filing the initial report, you have a heightened responsibility to be objective and detailed in your observations.